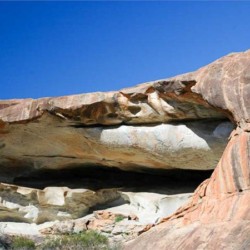

East and north of WA’s farming areas is a magnificent 16 million hectares (40 million acres) of relatively intact bush. It’s a rich tapestry of tall open woodlands, mallees and shrubby plains, granite rock islands, ironstone ridges, red dirt and searing salt lakes. This mosaic of vegetation connects Australia’s south-western corner to its inland deserts.

Nowhere else on earth does such a variety of large trees grow where water is so scarce and the soil so depleted of nutrients.

The Great Western Woodlands (GWW) is home to more than 20% of all Australia’s known plant species and remains a unique haven for communities of animal species that are now lost from elsewhere in Australia. These include many of the birds once typically found in temperate woodlands, but now declining in other parts of Australia. Its a place where these birds can continue to flourish in healthy woodlands, and we can learn nationally significant lessons on how intact woodland bird communities function.

These woodlands even still interact well with the climate – scientific monitoring along the western edge, where they adjoin the cleared wheatbelt, has demonstrated that clouds gather above the woodlands in response to the vegetation beneath, but following clearing are now often absent above the adjacent farmlands.

These realities are even more exciting when you appreciate that the area of the Woodlands is a source of significant commercial wealth. There are four towns, Kalgoorlie, Coolgardie, Kambalda and Norseman, and the woodlands are dotted with minesites, some small, some amongst the world’s largest, yet still retain a large degree of ecological functionality. The challenge is maintain or increase that level of functionality as mining continues, and if some stresses continue unabated, particularly in the face of a changing climate.

Stresses

Much of the Great Western Woodlands remains a largely intact and functioning ecosystem, and some areas are beginning to get some ecological management. There a small number of national parks and nature reserves, covering about 13% of the area, and the Ngadju Indigenous Protected Area, proclaimed in 2020, covers about 27%. An additional 20% is grazing lease.

The low level of ecological management is being reflected by increasing levels of damage being done to the woodlands. Wildfires have steadily increased since the mid-1980s, seemingly as a result of the drying climate, but there are still too few resources on the ground to tackle fires while they are small and relatively easy to contain. In 2019/2020 alone large intense wildfires burnt over 1.2million hectares, much of it old growth woodland (2-500 plus years). Feral animals, particularly wild camels and donkeys, seem to be steadily increasing, and Ngadju Conservation have already dealt with a number of invasive weed outbreaks, including Noogurra Burr. Unremediated mining and exploration sites remain erosion hazards, and ghost holes (uncapped drill holes) continue to kill native wildlife. The number of roads and associated gravel pits is steadily increasing, in the absence of an overall plan that assesses cumulative impact.

Its ecological connectivity with the rest of south-western Australia is being further damaged, with construction of over 600kms of ‘Barrier Fence’ along the southern boundary. This fence, is designed to stop emu and dingo movement, and is not considered by us to have the level of ecological assessment required.

Our vision

For the Woodlands we are seeking recognition, protection and integrated management for one of Australia’s great natural areas through the involvement of local communities for the benefit of people, nature and future generations. Already a number of organisations are working with the communities and stakeholders of the Woodlands to have this area protected, managed and promoted in a way that:

- Recognises and manages the area as a single entity (or landscape), not as fragmented, separate parts.

- Provides substantial financial and human resources for ongoing management.

- Supports ongoing, well managed, economic and recreational land uses.

- Ensures the rights of the area’s First Nations people are respected and supported, and they are enabled to have a high level of leadership in the ownership, management and protection of the areas culture and natural heritage.

- Highlights the area’s status as a very special, diverse and beautiful Australian landscape.

The story so far

In 2002 the immense natural values of the ‘bush beyond the fence’ were largely unrecognised. In 2003 we gained funding that enabled the Wilderness Society to begin a focus on the area, and their Wild Country program gained additional dollars for some detailed on-ground surveys. By 2008 they had produced an excellent booklet – the Extraordinary Nature of the Great Western Woodlands – which established both the name and the importance of this wonderful area. That same year bi-partisan political support was achieved, and the incoming Barnett government committed to improved management.

By 2010 a ‘Biodiversity and Cultural Conservation Strategy for the Great Western Woodlands’ had been developed and released by the State Government, but the initial funding for implementation was soon spent and little on-ground action has resulted.

Fortunately, in 2014 the Federal Court recognised the Ngadju’s people’s Exclusive Native Title over 4.4 million hectares of the Woodlands, and we have been able to focus considerable funding and effort into helping Ngadju Conservation Aboriginal Corporation establish a significant management presence. Similarly, the Esperance Tjaltjraak Native Title Aboriginal Corporation has established a land use agreement with the state government over some 800,000 hectares of the southern Great Western Woodlands, and Gondwana Link has been able to assist them to develop their Healthy Country plan covering the area.

Despite inactivity by government, the Great Western Woodlands is now a source of local pride and has a growing identify and presence with the general public. There has been a range of important scientific studies undertaken, perhaps foremost among these has been the ongoing volunteer bird surveys led by Birdlife Australia, and the immensely significant fire research undertaken by CSIRO and DBCA. This work has demonstrated the low flammability and high biodiversity levels of old growth woodland, as opposed to the high flammability of post fire woodlands.

Public support for the woodlands is producing some tangible results. Proposals in 2014 by two southern Shires for the allocation of some 500,000 hectares of the woodlands for farming failed to proceed within months of becoming known publicly. Efforts by a company to mine a section of Bungalbin (Helena-Aurora Range) were rejected by the state government, after a number of years of public campaigns opposing the mine. The area is now proposed to become national park. In 2020 two new proposals to extend Frank Hann and Peak Charles National Park were announced by the state government, and discussions on these is now underway with Ngadju and Tjaltjraak people. Again in 2020, Shire of Dundas has established a Woodlands interpretive centre in Norseman and proudly proclaim themselves as ‘the heart of the Woodlands’.

While disappointed that the State Government has failed to take a major ongoing role in the recognition, planning and increased ecological management of the Woodlands, we remain encouraged by the steady increase in public support and on ground changes being achieved.

More on the Great Western Woodlands:

About

Biodiversity

Culture and Heritage

Achievements

Research and Reports

Stop and rethink the fence