“Fire is a part of us, we are a part of it”, says Elder Uncle Eugene Eades. It has been a long time since the Goreng and Menang people of the Great Southern gave fire back to Country in the Noongar way. In this story, Gondwana Link’s JIM UNDERWOOD describes his experience as a non-Aboriginal member of a collaborative team that has supported a recent cultural burn on Country. Jim also offers intriguing insights into the challenges and opportunities that arise when Noongar people, ecologists and government agencies work together.

By Jim Underwood

Before colonisation, fire was one of the most powerful tools used by the Indigenous people of Australia to fulfil their cultural responsibilities to care for their Country. In WA’s Great Southern region, this use of fire fundamentally influenced the evolution of rich and resilient ecosystems.

But for many generations now, Noongar people have been denied access to land and the right to continue their custodianship. While the benefits of cultural burning for biodiversity, carbon sequestration and human safety have been well documented in other parts of Australia, in the Great Southern the inclusion of Noongar people and their knowledge to improve fire management has lagged behind. Because the wellbeing of First Nations peoples is so closely tied to the health of their Country, this lack of involvement has had detrimental impacts not only on the environment, but also on the health of Noongar people.

Despite this history of disempowerment, change is now afoot. With appropriate support from a range of organisations, Noongar groups across the Great Southern region are beginning a long journey of healing by putting ‘right fire’ back into the Country.

For those of us working east of Albany, early encouragement came with a visit in 2018 from Wiradjuri man Dean Freeman, Aboriginal Fire Officer from the ACT Parks and Conservation Service, and researcher Dr Jessica Weir, also from the ACT. They visited Ngadju and Noongar groups across Gondwana Link, sharing stories of successful cultural fire initiatives in eastern Australia which inspired many to keep pursuing these approaches.

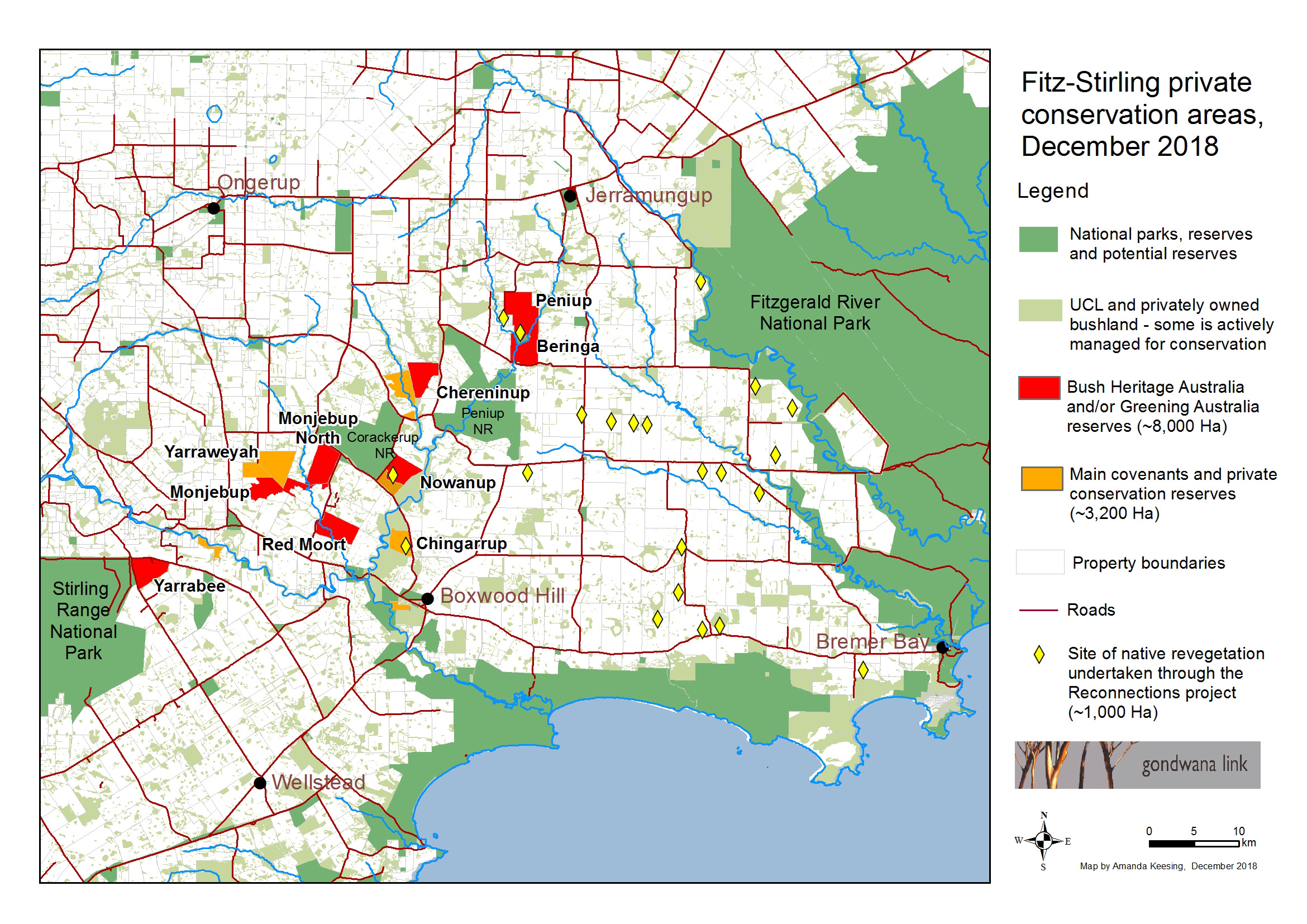

More recently, the Noongar managed property of Nowanup, in Goreng Country east of the Stirling Range, has been host to a series of gatherings to develop ‘right way’ partnerships that include Noongar people in decision making and implementation of fire management. These gatherings have drawn together more than 60 people from a broad range of organisations, cultures, and life experiences.

The participants comprised three main groups: 1) Noongar people from several families including Elders, community leaders and younger Rangers; 2) social ecologists from the University of Western Australia (UWA) and elsewhere; and 3) staff from both the Bushfire Centre of Excellence at the Department of Fire and Emergency Services (DFES), and the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA). In addition, farmers and local bushfire brigade members, conservation landholders, the Shire of Jerramungup, Gondwana Link staff and Friends of Nowanup joined the yarn.

The primary intention of these gatherings was to give respect and space for the Goreng and Menang Elders to share their stories, aspirations and knowledge. Despite such large groups, the non-Aboriginal people really listened to the Aunties and Uncles as they shared their relationship with fire (kaarl). All participants were particularly interested in how best to proceed with proposed prescribed burns in the nearby Peniup reserve. Peniup and Nowanup are biologically rich and form a critical part of the internationally significant Gondwana Link program that is reconnecting wildlife habitat between the Stirling Range and the Fitzgerald River National Parks. Peniup is an unvested reserve and may well become part of the Noongar estate after the South-West Native Title Settlement.

Discussions were held in a yarning circle – an Indigenous based way of relating that includes protocols of mutual respect, active listening and storytelling. This traditional way of meeting is much more than a debate and is a widely recognised and powerful method to share old knowledge and generate new knowledge by bringing people’s hearts and minds together. As Uncle Eugene puts it: “We want to make the old way become the new way by handing this knowledge down to our younger generation coming through. And when I say hand it down, I’m talking about non-Aboriginal people as well as Noongars. That’s a way of walking forward together.”

Yarning often works best on-Country. In the Great Southern, UWA’s researchers from the “Walking Together” project have been encouraging and documenting this approach to knowledge sharing for several years now. PhD candidate from UWA Ursula Rodrigues says, “Being on Country provides the space and time to listen to Country and for the Elders to reconnect to these places, which naturally reveals where in the landscape cultural burning is appropriate”.

Our series of yarning events went through three important phases: 1) attempting to understand conflicting perspectives, 2) finding common ground, and 3) taking action.

1. Attempts to understand conflicting perspectives

At times in the yarns, the legal and logistical factors that the government must account for when planning and implementing prescribed burns appeared at odds with the Noongar historical experience and their traditional and contemporary values.

Government agencies prioritise strategies for bushfire mitigation that aim to minimise the impact of large, hot and uncontrollable wildfires on human life and property, as well as natural ecosystems. In contrast, the Elders talked about the importance of using fire to rejuvenate the health of all life, as well as protecting bush foods, bush medicines and significant cultural sites. The yarning participants heard that in the old times, fires were mostly implemented through small, slow burns that were based on vast and intricate knowledge of Country and weather. In a similar way, the ecologists placed great value on the protection of vulnerable plant communities and the subtle variations in different ecological communities.

At one stage, non-Aboriginal participants had to stop talking and just listen to the Elders again. Uncle Aden Eades articulated the Elders were feeling like their “tyres were going flat” and their presence was token. This conversation centred on the need to properly fund a thorough cultural assessment before any burn.

Although it’s important not to simplify the nuances of the yarns, one way to look at it is that these different values relate to differences in scale of approach. For cost-efficiency, the state government’s statutory obligation to burn for wildfire risk mitigation means prescribed burns are usually implemented over large scales. In contrast, the preferred burning regime of Noongars and ecologists is through a network of smaller burns that consider and respond to fine-scale influences

2. Finding common ground

Working through these differences in values required honesty, persistence and forgiveness. Alongside these differences, there was some important common ground among the three groups of participants. Everyone agreed that a combination of habitat fragmentation, climate change and the history of Noongar exclusion means that a shift in approach is now needed to improve fire management in this region.

We also agreed there is plenty of room for improvement to bolster the health of the area’s exquisite ecological values and keep human communities as safe as possible. Indeed, human safety was of highest concern for all three groups in the yarning circle. The Elders explained that traditional ways with fire involved serious responsibility to keep burns under control.

We also heard about, and many appreciated, DBCA’s proposal for fire management in Peniup reserve. This could involve burning patches of bush which would provide safe buffer zones to aid cultural burning in the following year. Finally, we observed that, if properly trained and funded, Noongar Ranger teams can provide the necessary numbers of “boots on the ground” to implement finer scale burns.

3. Taking action

A third stage emerged where participants in the yarns all noted that just talking is not enough — we had to do something. Aunty Carol Pettersen stated, and the other Elders agreed, that “if the next meeting was to be just talking again, she didn’t want to be a part of it.”

Our ‘taking action’ involved a preliminary eco-cultural assessment of a small area at Peniup, where expertise from local ecologists was combined with Noongar knowledge. The team focused on the creek line and ended up surveying about five hectares. We found a lot of medicinal and food plants, some stone artefacts and special ochre cliffs. We also decided as a collective that it was time for a cultural burn led by the Elders on Nowanup.

On the appointed day in June 2022 the weather was perfect, with a light northerly wind and clear skies. The collaborative spirit was strong: DFES provided culturally sensitive guidance including the necessary fire control equipment and a burn plan; UWA provided ecological monitoring and handled most of the documentation; and Gondwana Link supported with other logistics. With this support, the Aunties and Uncles felt comfortable to give fire back to Country for the first time in many, many years. There were tears of joy as the burns were conducted under the watchful eyes of the old people on Boola Miyel (Bluff Knoll in Koi Kyenunu-ruff — the Stirling Range). The burns were undertaken in several locations that included open grasslands and mallee woodlands.

Everyone’s understanding of factors influencing fire behaviour in these ecosystems was improved, as was the first hand experience of the cultural values and ecological knowledge held by the Elders.

After the burn, David Windsor from DFES commented that “the cultural burns… demonstrated our program in action. It enabled cultural burning on Country, strengthened our networks and relationships and supported knowledge sharing.”

Other recent collaborations in Boxwood Hill, Manypeaks and Denmark have also brought together Noongar people, UWA, DFES, Shires and local bushfire brigades, highlighting the gathering momentum of cross-cultural burning initiatives across the Great Southern. Elsewhere in southern WA there has also been solid work undertaken in Indigenous fire management by the communities of Ngadju (centred in Norseman), Wadandi (centred in Busselton) and Tjaltjraak (centred in Esperance).

Summer bushfires are dangerous, and they are becoming more so with climate change and habitat degradation. As Uncle Eugene says, “Western people have been trying to tame the land but keep coming runner up. We need to listen to the land — let the Country lead again”. Here in south-western Australia the original custodians have survived colonisation and are now willing and able to share their knowledge and value systems. Community leader Rocky Eades summed it up this way, “While the Elders are still with us, it’s important we continue sharing their knowledge in these types of ways. We as Noongar people want to work as one with other agencies to not only look after our cultural assets, but also the land and all the people.”

For funding and in-kind support, Gondwana Link sincerely thanks the WA Government’s State NRM Program, Highways and Byways, Lotterywest Community Investment Framework, UWA, DFES Bushfire Centre of Excellence, Greening Australia, Bush Heritage Australia, DBCA and Friends of Nowanup.

Special thanks to all the participants in this story, and the photographers.